Wolf in Luneburg Heath

With his eyes fixed to the ground, Lucas Ende concentrates on the tracks before his feet. Ende works for the project on wolves at the Nature Conservation Association Germany (NABU) and searches the path for tracks of wolves. The sun is shining, the air is clear and the prints of wild boar, doe, badger and dogs behind the Groß Briesen – a village in the nature conservation area in “Hoher Fläming” at the southernmost tip of Brandenburg are easy to read.

Lucas Ende, NABU, measuring a wolf track, Hoher Fläming, Brandenburg

We take a turn to a lesser used forest path. Suddenly there is tension in the air, the track in front of us is different than the ones we saw before. Eyes fixed on the ground we walk along the path. The biologist measures the prints with a folding rule. He marks the tracks with sticks to identify a possible pattern. “Nine inches long, eight inches wide, the stride length is more than a meter” is the result of his measurement. The overall impression of the track fits as well: it is oval and not roundish as those of dogs, the mid-phalanx is less pronounced, the claw marks are sharp and point to the front. This is different from a dog track. The conservationist has no doubt: “a wolf came along this path”.

Track of a wolf, Hoher Fläming, Brandenburg

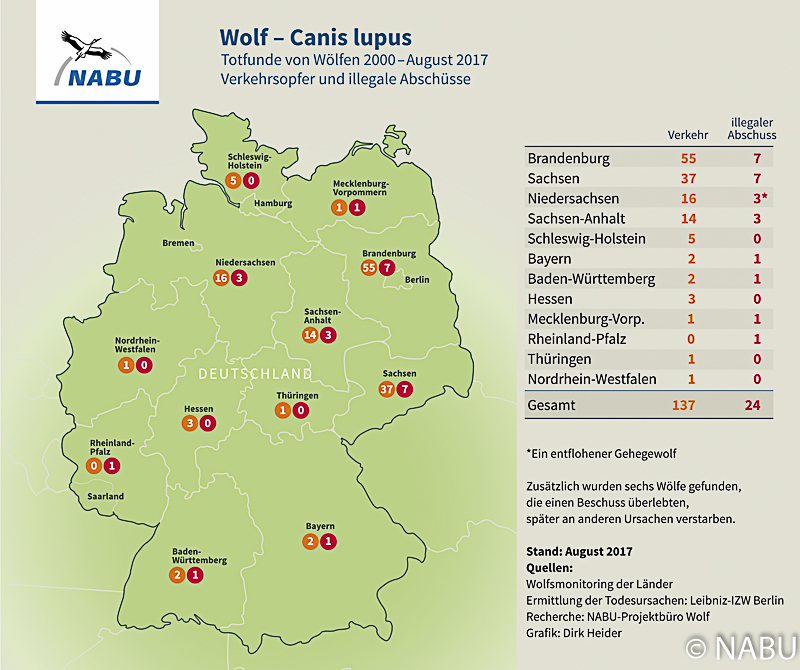

Wolves do not use animal crossings – at the most they cross them. The long-legged hunter prefers to roam on man-made roads and paths, because they can move energy efficient and fast. Their active phase in winter starts at twilight which coincides with rush hour traffic. Which poses a threat to young and inexperienced wolves. Since their return to Germany, 158 wolves have lost their lives on roads.

Wolves found dead, 2000 – 2017, victims of traffic or illegal killings

“Our” wolf has moved in a straight track. He swung slightly to the left towards a crooked pine once. Maybe the animal has tried to sniff something out. “If a male had marked his territory, we could identify that clearly according to the tracks it left,” Ende explains.

Wolf track in snow

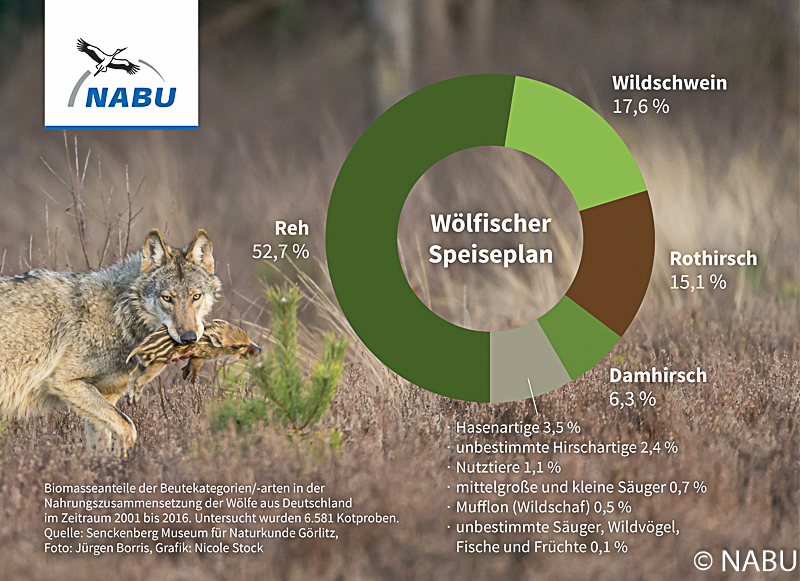

Particularly the droppings of the wolves give important hints about their food habits and their genetic origin as well as their migration patterns. Today we do not find clear signs. The feces in front of us seems mossy and quite old and cannot be identified clearly. The biologist explains “we know that wolves in Germany feed mainly on deer, in Poland rather red deer,”. Their diet also includes wild boar, hares and other small animals. Scientists equip some of the wolves with transmitters – it helps them to evaluate mobility data. Photographs from photo traps also help.

Wolf diet in Germany

According to an unpublished study by the Lupus Institute for Wolf Monitoring and Research in Germany, wolves avoid human settlements and agricultural areas. The animals rather pass those areas at night. Healthy wolves to not seek the vicinity of humans. The NABU expert explains that wolves sometimes show interest in dogs because they see them as food competitors or in rare cases as mating partners. However, if a dog walks close to its keeper during a walk, a wolf usually backs off.

Pups in moorland

At the end of January until the end of February wolves have their mating season. The animals are particularly active during that time and travel long distances through their territory. After about 60 days the female gives birth to her cubs in a den which is the focal area of family life for about thre months, then the youngsters follow the adults on their hunts.

Wolf in Luneburg Heath

Once a pair raises their first young it is called a pack. It includes the parents and all the offspring: the current litter and youngsters up to two years of age. The older cubs support the parents. They participate in hunting and babysit the little ones. At about two years of age, wolves are sexually mature. Young wolves leave the pack at the age of 10 months to two years. Regulating factors that determine the number of wolves in an area are the availability of food, the high mortality of juvenile wolves and youngsters leaving the pack.

Wolf, Daubitzer Pack

Young wolves can travel long distances on their journeys. Once they have found a partner, they occupy a territory where they settle. It can cover 200 square kilometers and more. The wolves do not need wilderness areas. They live wherever they can find enough prey and hideouts to raise their young without being interrupted by humans or busy roads. Therefore wolves can be found in nature reserves as well as military training areas, former mining areas or monocultures. The animals take their chance wherever an opportunity arises. For the conservationist, the wolf is an “intelligent but not sneaky, energy-efficient animal that ensures its survival by adapting its behavior.”

Forest road with wolf track, Hoher Fläming, Brandenburg

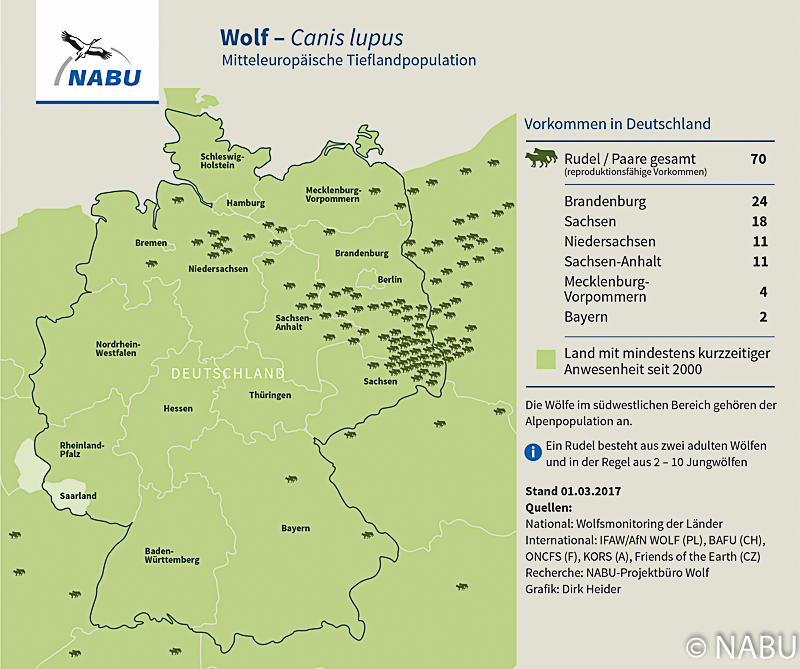

Around 1850 the gray dogs disappeared in Brandenburg. The last wild wolf was killed about 150 years ago in Germany. Until the 1980s, people shot wolves migrating in from the east because it was legal – in East Germany even longer. The European Union protected the wolf in the early 1990s. In 1998, the first pair from Eastern Poland successfully established itself on the military training area Oberlausitz in Saxony. Two years later the first litter was born. The big hunters migrated from Saxony via Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt to Lower Saxony. Resident wolves have been documented in Brandenburg since 2006.

Distribution of wolfes, Germany

Meanwhile three pairs and 22 packs with 74 cubs have been documented here by the Federation’s Documentation and Advice Center on the Subject of Wolves (DBBW). According to the center a total of 60 packs with 218 puppies, 13 pairs and three territorial individuals lived in the federal states of Bavaria, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia in the wolf year 2016/2017.

Wolves in lake area, Lausitz

This marks an incredible success story of the voluntary return of the silent hunters. On the other hand – as soon as the wolf has set its paws back on German soil and has established a pack, resistance rises. Suddenly the deep fears and old dislike are back. Those opposing the wolf’s return claim that it endangers the population, the livestock and – last but not least – the wildlife. They even blame the animal for spreading the African swine fever. However, Ende explains that the disease is more likely spread by humans with their increased transport activities of goods from the East. The wolf can be excluded as a cause to nearly 100% which was confirmed by the Löffler Institute (responsible for the research of animal diseases) recently.

Wolf in moorland

The population of wolves is growing slowly but steadily in Germany which raises the question of carrying capacities and regulating numbers of wolves by those concerned by the return of the hunter. The wolf expert explains that “we are far away from a good state of preservation of the wolf population in Germany as the EU criteria indicate” and he continues that “nature regulates itself. The wolves adapt to what is available in terms of territories and prey animals.” The wolf expert at NABU appreciates the return of the gray hunters because “we have let the wolf as part of nature come back by itself despite our habits of using nature and our agricultural monocultures.”

![Deer crossing, pine forest, Hoher Fläming, Brandenburg[/caption]

[shariff] </div><!-- .entry-content -->

<footer class=](https://heikepander.com/content/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/P2010052.jpg) This entry was posted in Blog, Europe, Writing and tagged Brandenburg, Hoher Fläming, Lucas Ende, NABU, Rückkehr der Wölfe, Spurensuche, Wolf by Heike Pander. Bookmark the permalink.

This entry was posted in Blog, Europe, Writing and tagged Brandenburg, Hoher Fläming, Lucas Ende, NABU, Rückkehr der Wölfe, Spurensuche, Wolf by Heike Pander. Bookmark the permalink.